Domestication is more of a granular process than an endpoint, explains Thomas Lecocq, associate professor of animal biology and ecology at the University of Lorraine, France. And silk moths are extreme examples of what happens when it runs for millennia: they can’t complete their life cycle without us.

“In fact, it’s kind of a continuum of human-animal interaction… and within that you can say, ‘I’ve reached this level of domestication because I’m able to complete the entire life cycle of the organism in captivity,'” says Lecocq.

These clumsy “sky puppies,” as some call them, not only can’t fly — they’re sluggish, have poorer sense of smell, smaller brains, and even different gut microbiomes than their wild counterparts. Crucially, domesticated silkworms also produce other silk.

Silkworms weave their soft, perfectly egg-shaped cocoons with their mouthparts, which secrete a protein-rich liquid that hardens as it exits. So the caterpillars wag their little heads around and literally pull them up in the air. They end up with a fluffy cocoon made from a single unbroken strand of silk about 915 m (3,300 ft) long – just under a kilometer.

In its raw form, silk is coated with a kind of glue that makes it stiff and rough to the touch. Not only do native silkworms produce larger, whiter cocoons, they also produce far less of that protein – sericin – which has to be removed as part of the manufacturing process.

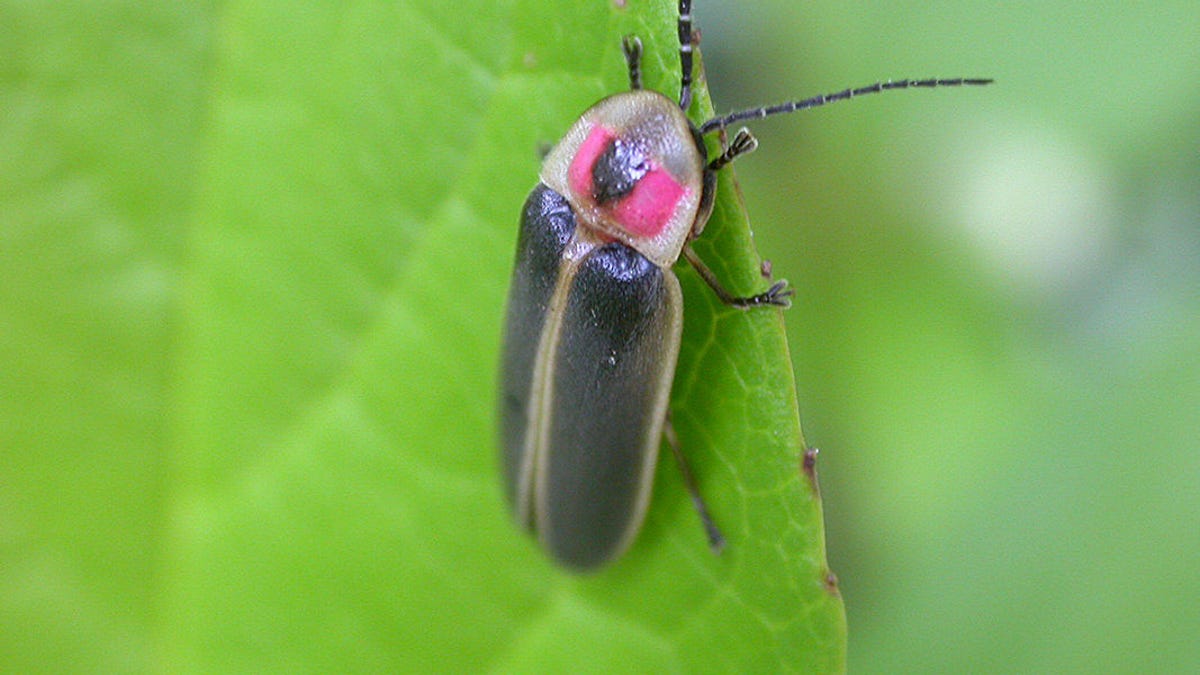

The wild Bombyx mandarina moth has changed so that its domesticated cousin Bombyx mori is now a different species. But not all domesticated insects have undergone such striking changes.

A tricky question

A queen has arrived on a farm in Wales. There’s no marching band, security, or patriotic crowd — indeed, this monarch suffered the humiliation of being special-delivered in a plastic box. She was allowed at least a team of courtiers to wait patiently beside her in the passenger area. At the other end is a large pile of powdered sugar.

She’s a honey bee, of course – a member of the noble Buckfast breed – and she and her companions have come to improve the productivity of an existing hive. After being unwrapped and placed between her new subjects, she will eat her way through the icing sugar plug and make her way into her bee palace.