These were not great florid beasts. But the alligators were, as expected, quite a spectacle in the often chilly New England.

There are several newspaper articles from this period referring to the alligators who lived in a basin – or pond – near the entrance to Arlington Street amid a “magnificent” row of lilies. Reports vary, but for some time there were between three and four alligators on the site, strikingly complementing the many other exotic features of the public garden at the time.

A story in the September 19, 1901 issue of the Boston Post said three of the city’s alligators were given by “a Charlestown woman” who “became afraid of them and introduced them to the city of Boston.” The fourth alligator was given to the city by a man from Chelsea, though it’s just unclear why.

An article that appeared in an August 9, 1901 issue of the Boston Globe said the alligators – known as babies – belonged to William Doogue, the city’s superintendent for common and public reasons.

Doogue oversaw the public garden from 1878 to 1906, according to Friends of the Public Garden, a nonprofit advocating Boston Common, the public garden, and the nearby Commonwealth Avenue Mall and known for its exceptional green thumb.

“Outspoken, media-aware and politically smart, Doogue was a consummate showman,” wrote the organization in a 2019 blog post about the history of the park. “He has been courting the press to promote his horticultural extravaganzas and defy critics who accused his flower displays of ‘gaudy’ bad taste.”

The alligators have certainly rubbed some city dwellers the wrong way. But it wasn’t so much their presence that was annoying – people often huddled around the pool looking for them – it was how they were sometimes fed.

“Some objections to feeding live rats and mice to those in the public garden pond,” read the headline of the August Globe article.

The newspaper reported that in “warm weather” the alligators were put in the public garden and fed by park officials once a week.

But residents often had other plans: to throw rodents that they had caught in traps to the alligators for fun. Hardly a top-class affair.

“Live rats exposed to hungry alligators,” read a headline in the Boston Post on August 9, 1901. “The public garden exhibit attracts morbid interest from women and children.”

The article says, “The city doesn’t feed them in the summer … the city doesn’t have to” because “the alligators make their own living by entertaining the public”.

The story included an illustration of primitively dressed people gathered around a small pond-like structure and watched a man kneel to feed the alligators with the animals’ mouths wide open.

A 1901 Boston Post news clip about the alligators.Boston Post

The article described in detail how the rodents were driven to their extinction.

“The victim is thrown into the pond,” it read. “As it splashes the water, the three alligators start walking towards it. Kicking and squeaking are drawn underwater … they fight violently, the mud is stirred from the bottom of the shallow pond. Then red spots appear through the muddy water. The crowd is slowly dispersing. The fun is over – for now. “

Some viewers were not enthusiastic about the vicious spectacle.

“Of course mice and rats have to be killed, but why should they be killed for fun in public?” A viewer of the Post was quoted as saying.

But others sided with the alligators, describing them as “the dearest, cutest little things in the world,” perhaps because “they’re so homely and stupid,” the Globe reported.

In fact, despite some protests against the live feedings, they seemed to have some kind of fan base.

A second Globe article, dated October 13, 1901, described how the alligators were removed from the park for the fall and winter months. It was an unforgettable sight that attracted curious people up close.

“Alligators hooked from the public garden,” read the headline. “Spent over three hours becoming the tallest of four.”

“The event of the week in the public garden was the removal of the alligators from their cheerful summer home in the well basin near the Commonwealth [Ave.] Tor, ”was the story.

According to reports, the alligators were then moved to their “winter quarters”, a greenhouse in Franklin Park in Dorchester.

1901 appeared in the Boston Globe news clips about the alligators.Boston Globe

1901 appeared in the Boston Globe news clips about the alligators.Boston Globe

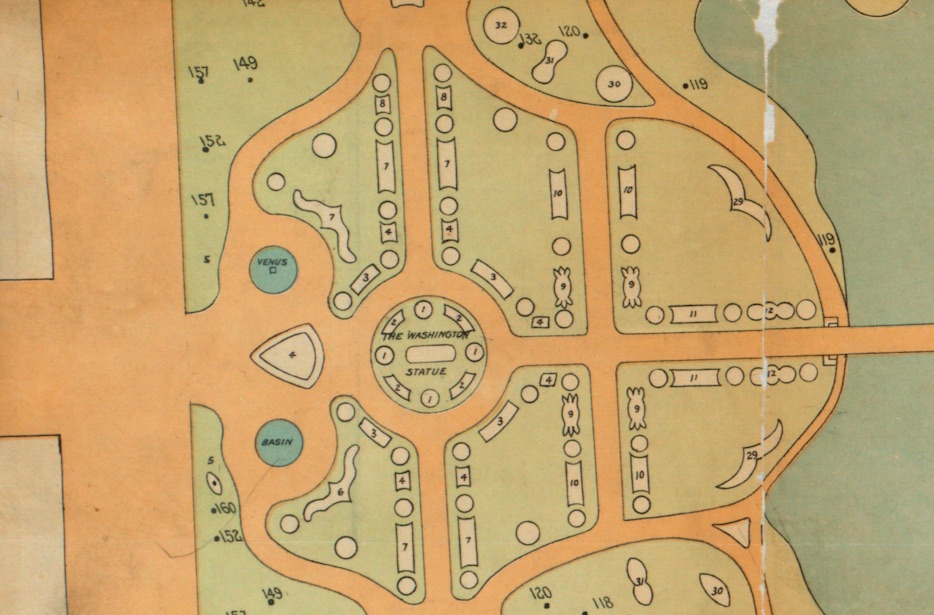

A 1901 map of Boston Common and the public garden on the Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center website shows a small, circular area in blue near the main gates. The point on the map is marked “basin,” the same term that the article uses to describe where the alligators were kept.

There is now a fountain called “Boy and Bird” that had the pool in it on the map. The structure is a stone’s throw from the George Washington statue that greets people as they enter the park. It is across from Commonwealth Ave., which intersects with Arlington Street. (An alligator reportedly got out of the car and walked halfway to the church on Arlington Street).

It’s not clear how long the alligators were on the site, but an article suggested that they may have been introduced by Doogue around 1900. A blurb in the globe from 1906 – just months before Doogue’s death – seemed to suggest that they had moved elsewhere in the park by then.

“This Boston zoo that was talked about a few months ago has not yet been realized,” it said. “But we can all go to Arlington-Beacon Street. Corner of the public garden and see the alligators. “

Partial map of the Boston Public Garden in 1901, including a “basin” where the alligators were reported to be.Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library

Partial map of the Boston Public Garden in 1901, including a “basin” where the alligators were reported to be.Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library

Boston Parks and Recreation Department officials said they had no additional information about the alligators. According to the Boston Guardian, which also published a story about the animals, from 1901 there was a $ 30.91 budget item from the Department of Public Land to be used for “food for cats, dogs, and alligators.” Friday.

Liz Vizza, president of Friends of the Public Garden, said in a statement that the organization “was amazed to learn” that Doogue, among his many other talents, kept alligators in the tank. She called it “a strange and wonderful story that has emerged from the past.”

But could history repeat itself?

“The alligators, usually an aquatic animal native to more tropical areas, might be just right with the tropical plants in the garden,” Vizza said jokingly.

Steve Annear can be reached at steve.annear@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @steveannear.