A big event in the insect world is approaching. From April or May, depending on latitude, one of the largest broods of 17-year-old cicadas will emerge from the underground in a dozen states, from New York west to Illinois and south to northern Georgia. This group is known as Brood X, as in the Roman numeral for 10.

For about four weeks, forest and suburban areas ring with whistling and humming mating calls from the cicadas. After mating, each female lays hundreds of eggs in pencil-sized branches.

Then the adult cicadas will die. As soon as the eggs hatch, new cicada nymphs fall from the trees and dig into the ground again, starting the cycle again.

There are perhaps 3,000 to 4,000 species of cicada around the world, but the 13- and 17-year-old periodic cicadas in the eastern United States appear to be unique in combining long juvenile development times with synchronized mass-adult emergences.

These events raise many questions for both entomologists and the public. What do cicadas do underground for 13 or 17 years? What are you eating? Why are their life cycles so long? Why are they synchronized? And does climate change affect this wonder of the insect world?

We study periodic cicadas to understand issues related to biodiversity, biogeography, behavior and ecology – evolution, natural history and the geographical distribution of life. We learned many surprising things about these insects: for example, they can travel through time changing their life cycles in four year increments. It is no coincidence that the scientific name for periodic 13- and 17-year-old cicadas is Magicicada, abbreviated from “magical cicada”.

Natural history

Periodic cicadas are species older than the forests in which they live. Molecular analysis has shown that the ancestor of the current Magicicada species split into two lineages about 4 million years ago. About 1.5 million years later, one of these lines split again. The resulting three lineages form the basis for the modern periodic cicada species groups Decim, Cassini and Decula.

Early American colonists first encountered periodic cicadas in Massachusetts. The sudden appearance of so many insects reminded them of biblical plagues of locusts, which are a type of locust. The name “grasshopper” was mistakenly associated with cicadas in North America.

During the 19th century renowned entomologists such as Benjamin Walsh, CV Riley and Charles Marlatt worked on the astonishing biology of periodic cicadas. They found that, unlike grasshoppers or other grasshoppers, cicadas do not chew leaves, decimate crops, or fly in flocks.

Instead, these insects spend most of their lives out of sight, growing underground and feeding on plant roots as they go through five stages of youth. Their synchronized appearances are predictable and occur after a clockwork of 17 years in the north and 13 years in the south and the Mississippi Valley. There are several regional annual classes known as broods.

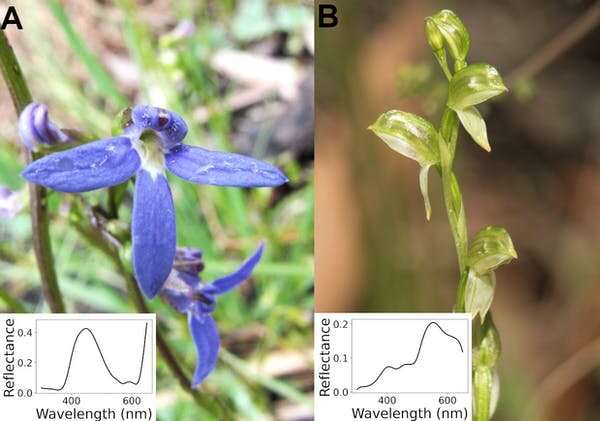

(Chris Simon / CC BY-ND)

BILD: The five stages of the periodic underground cicada juveniles. Between each stage, the juvenile cicada melts so it can grow larger. The actual size of the fifth stage nymph is 0.83 inches.

Security in numbers

The main characteristic of Magicicada biology is that these insects appear in large numbers. This increases their chances of fulfilling their top key task: finding partners.

Dense emergencies also provide what scientists call predatory satiety defenses. Any predator that feeds on cicadas, be it a fox, squirrel, bat, or bird, will eat its fill long before it consumes all of the insects in the area and leaves many survivors.

While periodic cicadas mostly appear on schedule every 17 or 13 years, a small group often shows up four years earlier or later. Early emerging cicadas can be faster growing individuals who have had access to abundant food, and the stragglers can be individuals who lived on less.

As growing conditions change over time, it is important that this type of life cycle can be toggled and come out either four years earlier in favorable times or four years late in difficult times.

If a sudden warm or cold phase causes a large number of cicadas to make a one-off mistake and deviate from the schedule by four years, the insects may appear in sufficient numbers to satiate predators and move on to a new schedule.

Cicada broods, identified by Roman numerals, arise in cycles of 13 or 17 years. (University of Connecticut, CC BY-ND)

Census time for Brood X.

When the glaciers retreated from what is now the United States about 10,000 to 20,000 years ago, periodic cicadas filled the eastern forests. The temporary switching of the life cycle has created a complex brood mosaic.

Today there are 12 broods of 17-year-old cicadas in northeastern deciduous forests where trees drop leaves in winter. These groups are numbered consecutively and fit together like a giant puzzle. There are three broods of 13-year-old cicadas in the southeast and the Mississippi Valley.

Since periodic cicadas are climate sensitive, the patterns of their broods and species reflect climatic changes. For example, genetic and other data from our work indicate that the 13-year-old species Magicicada neotredecim, found in the upper Mississippi Valley, formed shortly after the last glaciation.

As the environment warmed up, after 13 years underground, 17-year-old cicadas appeared one after the other in the region until they were permanently switched to a 13-year cycle.

However, it is not clear whether cicadas can evolve as quickly as humans change their environment. Although periodic cicadas prefer forest edges and thrive in suburbs, they cannot survive deforestation or reproduce in areas without trees.

In fact, some broods are already extinct. In the late 19th century, one brood (XXI) disappeared from northern Florida and Georgia. Another (XI) has been extinct in northeast Connecticut since about 1954, and a third (VII) in New York State has shrunk from eight to one county since mapping began in the mid-19th century.

Climate change could also have far-reaching effects. As the US climate warms, longer growing seasons can provide greater food supplies. This could eventually turn more 17-year-old cicadas into 13-year-old cicadas, just as warming in the past changed the Magicicada neotredecim.

Cincinnati and the Baltimore-Washington subway area, and the Chicago subway area in 1969, 2003, and 2020, saw large-scale early emergencies in 2017 – potential harbingers of this kind of change.

Researchers need detailed, high quality information in order to be able to track leaf hoppers distributions over time. Citizen scientists play a key role in this effort because the periodical populations of cicada are so large and their adult appearances last only a few weeks.

Volunteers who would like to document the creation of Brood X this spring can download the Cicada Safari mobile app, provide snapshots and follow our research in real time online at www.cicadas.uconn.edu. Don’t miss it – the next opportunity won’t come until Broods XIII and XIX show up in 2024.![]()

John Cooley, Assistant Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut; and Chris Simon, Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut.

This article is republished by The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.