For the past four years, journalists and environmental bloggers have been churning out story after story that insects are vanishing, in the United States and globally. Limited available evidence lends credence to reasonable concerns not least because insects are crucial components of many ecosystems.

But the issue has often been framed in catastrophic terms, with predictions of a near-inevitable and imminent ecological collapse that would undermine global biodiversity, destroy harvests and trigger widespread starvation. Most of the solutions would require a dramatic retooling of many aspects of modern life, from urbanization to agriculture.

Considering the disruptive economic and social trade-offs being demanded by some who promote the crisis hypothesis, it’s prudent to sperate genuine threats from agenda-driven hyperbole. How ecologically threatening are insect declines? Should we be in ‘catastrophic crisis’ mode? What should we as a collective society responsibly do?

Roots of the crisis narrative

The recent hyper-focus on insects traces back to a 2017 study conducted by an obscure German entomological society that claimed that flying insects in German nature reserves had decreased by 76 percent over just 26 years. The study, co-authored by twelve scientists, lit a fire in advocacy circles and became the sixth-most-discussed scientific paper of that year, and remains popular.

Headlines appeared around the world predicting an impending “ecological Armageddon” resulting from mass insect deaths, a turn of phrase offered by one of the co-authors, Dave Goulson. Then a relatively unknown English biology professor, Goulson rapidly became the public face of the crisis narrative. Although there was immediate and widespread skepticism in the entomology community, for the most part journalists appeared all-in with the ‘end of world’ narrative.

The New York Times Magazine’s Brooke Jarvis christened the study’s legitimacy, headlining its feature: ”The Insect Apocalypse Is Here” and promoting it with a visually stunning and frightening cover illustration.

The lengthy feature was filled with speculation about the imminent ‘complete’ disappearance of insects, using descriptors such as “chaos”, “collapse”, “ecological dark age” and “Armageddon”. Compounding the imminent catastrophe, our most despised pests, from cockroaches to house flies, would largely be spared, booming out of control as beneficial insects vanished.

The Times’ summary conclusion? The world is facing a loss of biodiversity, what it called the ‘sixth extinction. And it will get worse; the insect declines were the canary in the ecological mine. Goulson, a professor at the University of Sussex, was the featured scientist in the piece. The Times quoted him as choking up in grief as he shared his poignant, ‘end-of-life-as-we-know-it’ crisis scenario:

“If we lose insects, life on earth will. …” He trailed off, pausing for what felt like a long time.

The tsunami of crisis articles served as a wake-up call. But to what? A number of studies suggest that insect populations are declining in some areas of the world (but not in others) or that certain kinds of insects (taxa) may in decline in those regions (even as others are increasing). But Armageddon? Such catastrophic framing and the policy implications that would inevitably flow from that conclusion are significant.

Perhaps the inflammatory rhetoric, which continues today, is justified. Or maybe not. Certainly, entomologists and insect ecologists all over the world need more support and funding to fully evaluate concerns. But many scientists believe what should be an evidence-driven evaluation has morphed into an ideological litmus test for the environmental media and advocacy-focused scientists.

Insectageddon is a great read. But what are the facts?

The Times essay read like a convincing polemic, but the ‘catastrophe narrative’ fell flat with the science community, which has spent much of the last four years trying to tame the consequent hysteria.

What is the consensus view? Manu Sanders is a prominent entomologist, recipient of the Office of Environment & Heritage/Ecological Society of Australia Award for Outstanding Science Outreach. She and colleagues Jasmine Janes and James O’Hanlon outlined the science-based perspective in 2019 in BioScience, where they examined the headline-grabbing apocalypse studies that had appeared to that date. They summarized their conclusions in a post for Ecology Is Not a Dirty Word, a highly respected blog that Saunders oversees:

We summarise the major flaws in the pop culture ‘insect apocalypse’ narrative and argue that focusing on a hyped global apocalypse narrative distracts us from the more important insect conservation issues that we can tackle right now. Promoting this narrative as fact also sends the wrong message about how science works, and could have huge impacts on public understanding of science. … And, frankly, it’s just depressing.

Of one of the major studies used to promote the apocalypse narrative (“Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers”, by Sanchez-Bayo and Wychkhuys, discussed below), Sanders noted an appallingly selective and apparently willful misrepresentation and manipulation of the data:

From a scientific perspective, there is so much wrong with the paper, it really shouldn’t have been published in its current form: the biased search method, the cherry-picked studies, the absence of any real quantitative data to back up the bizarre 40% extinction rate that appears in the abstract (we don’t even have population data for 40% of the world’s insect species), and the errors in the reference list. And it was presented as a ‘comprehensive review’ and a ‘meta-analysis’, even though it is neither.

Reflecting broad concerns among ecologists, Saunders also worried about the failure of prominent news organizations like the New York Times to treat alarmist claims with proper skepticism, and argued that ideological group-think had captured the media on this issue:

Most journalists I spoke to have been great, and really understand the importance of getting the facts straight. But a few seemed confused when they realized I wasn’t agreeing with the apocalyptic narrative – ‘other scientists are confirming this, so why aren’t you?’

Professor Sanders has written a stunning 4-part series on what she sees as the manipulation by narrative-promoting journalists and scientists [see: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4].

Roots of the crisis narrative

It’s important to understand how we got from the consensus ‘there is fragmentary but concerning evidence’ of insect declines to ‘the world faces imminent collapse’. The global insect crisis narrative dates back more than a decade, and was originally focused on alarming reports beginning in 2006 of a surge in honeybee mortality.

The die-offs, concentrated mostly along the west coast of the US, were dubbed Colony Collapse Disorder. CCD is an enigmatic condition that causes bees to vanish without a clear explanation. At the time, many environmental activists claimed it was the early signs of a ‘bee-apocalypse’, blamed insecticides as the root cause, a conclusion widely circulated by the media.

Then as now, the mainstream entomology community (and even a special task force set up by President Obama’s USDA) tried to push back on the crisis narrative. Incidents similar to CCD (previously known as ‘disappearing disease’) had occurred in the 1800s and 1900s, long before synthetic pesticides were invented. This iteration of CCD had largely ended by the early 2010s, experts say.

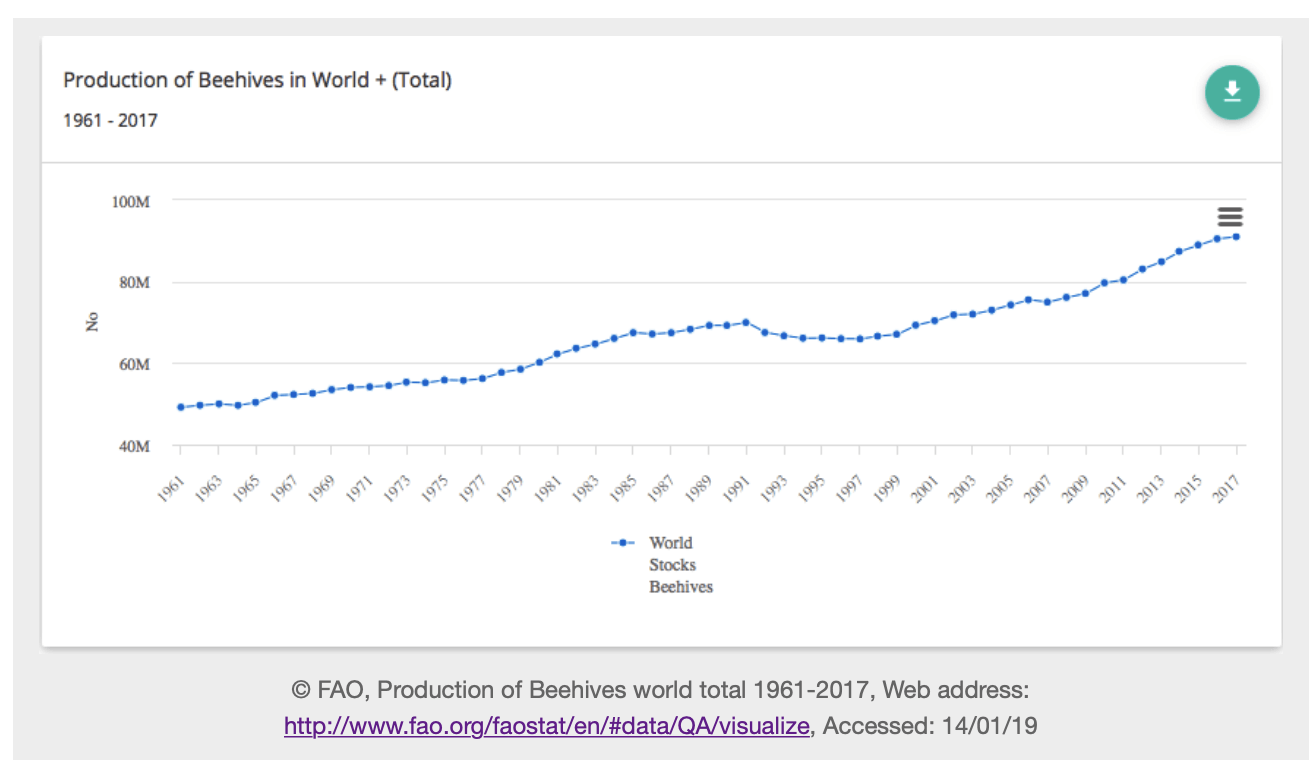

Honey bee colony levels have remained stable despite elevated loss rates.

But that’s not the story that dominated headlines. The ‘media crisis’ persisted for years, cresting in an article not by The Times but by Time, which proclaimed in a 2013 cover story: “A World Without Bees: The Price We’ll Pay If We Don’t Figure Out What’s Killing the Honeybee”

But by then, the crisis had passed; honeybee populations had begun to stabilize, and by 2015, they hit a 20 year high in the US. This trend held globally: honeybee populations have increased 30 percent worldwide since 2000.

By 2018, almost every major news organization, from the Washington Post (‘’Believe it or not, the bees are doing just fine”) to Slate (‘The Bees are Alright”) and including many environmental publications such as Grist (“Why the bee crisis isn’t as bad as you think’) were sheepishly acknowledging there never was an imminent worldwide honeybee catastrophe. The New York Times was conspicuously one of the few news outlets to not reconsider its crisis narrative.

How healthy are bees? As the Genetic Literacy Project has previously reported (here, here and here), dire predictions of an impending insect extinction rest on studies that suffer from flawed methodologies and are based on fragmentary and mostly regional data.

While honeybees face health challenges, that’s in part because they are “pack animals” trucked around from one region to another to pollinate crops. Their ongoing health problems are primarily linked to the spread of disease-carrying Varroa mites.

There is fragmentary evidence of health challenges facing wild bees, which are notoriously hard to evaluate. But a worldwide pollinator crisis caused by insecticide overuse, as Goulson and others claim? The most comprehensive recent study, released in May 2021, found few of 250 bumblebee species from around the world were in peril, challenging the apocalypse narrative. “If you look at all the species, on average, there is no decline,” concludes ecologist Laura Melissa Guzman at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia.

Even the hardline Sierra Club was forced (briefly) to do an about face. In 2016 (well after other news organizations had revised their crisis narrative), the group’s “save the bees” fund raising campaign mailer was still dominated by media-hyped hysteria:

Bees had a devastating year. 44% of colonies killed…and Bayer and Syngenta are still flooding your land with bee-killing toxic ‘neonic’ pesticides—now among the most widely used crop sprays in the country.

Challenged by the GLP, and as the tide of mainstream environmentalists turned against the bee apocalypse narrative, Sierra Club, with no mea culpa or even an explanation, suddenly reversed itself in 2018, posting a far different message on its blog:

Honeybees are at no risk of dying off. While diseases, parasites and other threats are certainly real problems for beekeepers, the total number of managed honeybees worldwide has risen 45% over the last half century.

Even as ‘beepocalypse’ mongering faded in the science community, many environmental groups, often citing Goulson (an ardent early promoter of the honeybee catastrophe false narrative), gish-galloped over to claims that wild bees, then birds, and now all of the insect world face extinction.

That’s what happened at the Sierra Club. Within months of its reversal on honeybees, in yet another campaign asking for more contributions to protect bees, the once venerable environmental group was touting Goulson’s broader insect Armageddon claims, again fingering “pesticides” as the driving culprit.

Are pesticides the problem?

Those exaggerations have been challenged repeatedly by high-quality papers and real-world evidence. But while claims of pending “-pocalypses” occasionally have been walked back by the media, rarely has this been done with the same gusto with which they headlined each successive “Armageddon”.

In August, Dave Goulson will be releasing a documentary that he wrote and narrated, “Insect O Cide”. As described by the London Post, “The central theme of the film is that human beings are on the verge of extinction due to the rapid decline in the insect populations.”

The documentary will arrive just in time to promote the September release of Goulson’s latest book, Silent Earth: Averting the Insect Apocalypse, which aspires to be a modern-day Silent Spring. It’s clear, he claims, what is to blame for this imminent extinction: “The main cause of this decrease in insect populations is the indiscriminate use of chemical pesticides.”

Dave Goulson has a controversial reputation in the science community. As the GLP has previously reported, he is an admitted scientist-for-hire, who has produced research with a promised, pre-determined conclusion for activist organizations. His views, dating back a decade now and seemingly impervious to new evidence, have not changed: he vociferously lambasts the use of advanced technology in farming, from genetic engineering to the use of targeted synthetic, specifically targeting the class of pesticides known as neonicotinoids — while ignoring the ecological impact of organic pesticides.

As he told The Guardian at the time of the publication of his controversial 2017 study, “[The insect deaths could be caused by] exposure to chemical pesticides,” even though the study sampled populations from nature reserves and its purpose wasn’t to detect causes of declines.

The Goulson et al. conclusion was prominently amplified in 2019 in a meta-analysis of insect population trends around the world by Francisco Sánchez-Bayo (I’ve previously discussed the study in depth here). In an interview with The Guardian, Sánchez-Bayo went so far as to claim insects will disappear from the Earth in a century:

The 2.5% rate of annual loss over the last 25-30 years is ‘shocking’, Sánchez-Bayo told the Guardian: ‘It is very rapid. In 10 years you will have a quarter less, in 50 years only half left and in 100 years you will have none.’ One of the biggest impacts of insect loss is on the many birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish that eat insects. ‘If this food source is taken away, all these animals starve to death.’

That’s a frightening scenario, which Sánchez-Bayo argued was due to “industrial-scale, intensive agriculture.” But that conclusion was not supported by the evidence in his paper and was criticized by the entomology community. While some of the studies included in the meta-analysis were related to agriculture, and some speculated pesticides were responsible for declines, that was his personal opinion, voiced without data, yet cited by many reporters as the main ‘take away’ from the study.

As Manu Sanders noted in American Scientist, the Sánchez-Bayo study was beset by numerous major methodological errors. The authors only included studies that specifically mentioned the phrase” insect declines,” thus biasing the results, as some reports of stable or rising populations were excluded from the analysis.

While Sánchez-Bayo was claiming “almost half of the [world’s insect] species are rapidly declining, their data documented declines for about 2,900 species, a tiny fraction, less than 1/10th of 1%) of the insect species on Earth. As Sanders and others noted, while about 900,000 species of insects have been identified globally, studies of Latin American forest canopies have suggested there may be upwards of 30 million insect species.

Sánchez-Bayo et al. also claimed that their research was based on a “worldwide” assessment, but nearly all of the data were drawn from the US and Europe. There could be as many as 200,000 insect species in Australia alone, but data from that country focused solely on managed honeybees. The statistics from Asia (excluding Japan) only included managed beehives and there were no studies from Central Africa and almost none from South America, a global insect population epicenter.

Excluding data from some of the most ecologically diverse regions on the planet, along with studies on increasing or stable insect populations, biased the study so severely that its results cannot be used to draw any conclusions on changes in insect populations worldwide.

Geographic location of the 73 reports studied on the world map. Columns show the relative proportion of surveys for each taxa as indicated by different colors in the legend. Data for China and Queensland (Australia) refer to managed honeybees only.

Geographic location of the 73 reports studied on the world map. Columns show the relative proportion of surveys for each taxa as indicated by different colors in the legend. Data for China and Queensland (Australia) refer to managed honeybees only.

What do mainstream insect experts conclude?

The silver lining from the recent spate of advocacy-focused studies news is that entomologists are doing a deeper dive into the reasons behind the global declines. Goulson’s upcoming media blitz notwithstanding, the most thorough studies to date on insects in North America challenges the catastrophe narrative (although you may not have heard about them as they have been almost ignored by the media), and even offers some reassuring news.

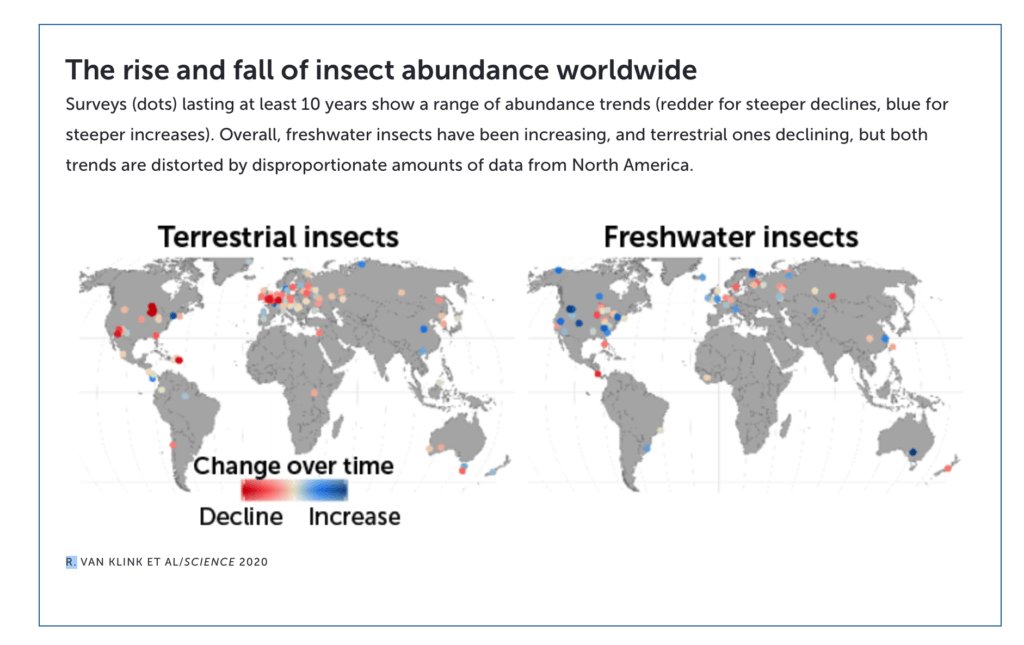

A 2020 study by German researchers led by Dr. Roel van Klink represented the largest and most definitive study on global insect populations at the time of its publication. The meta-analysis of 166 studies found that insects are declining much less rapidly (3- to 6-fold less) than previously reported, and freshwater insects are actually increasing. Other major findings:

- The only correlation with insect declines was habitat, specifically urbanization

- Cropland was correlated with insect abundance

- Insect declines in North America ended by the year 2000

While comprehensive, the report wasn’t flawless. The primary issue, shared with Sánchez-Bayo, was that nearly all data came from Europe and North America. As the below map shows, there were only a few studies from South America and Africa, and none from South Asia, making it impossible to declare whether insects are declining or increasing in those regions.

While threats to certain species do exist in certain locations, that doesn’t support claims that we face a broad, global population collapse among insects.

North American insect populations are stable

The deficiencies of these studies when it came to identifying global trends encouraged a team of 12 researchers led by Matthew Moran at Hendrix College in Arkansas to examine the situation in North America. As the authors noted, “much evidence for what has been dubbed the ‘insect apocalypse’ comes from Europe, where humans have intensively managed landscapes for centuries and human population densities are particularly high.” They wondered if examining the extensive data collected on the geographically and ecologically diverse North American continent would yield the same or a different conclusion.

Students from Moran’s laboratory oat Hendrix College sampling insects at a prairie in Arkansas using a suction machine.

Students from Moran’s laboratory oat Hendrix College sampling insects at a prairie in Arkansas using a suction machine.

Students from Moran’s laboratory oat Hendrix College sampling insects at a prairie in Arkansas using a suction machine

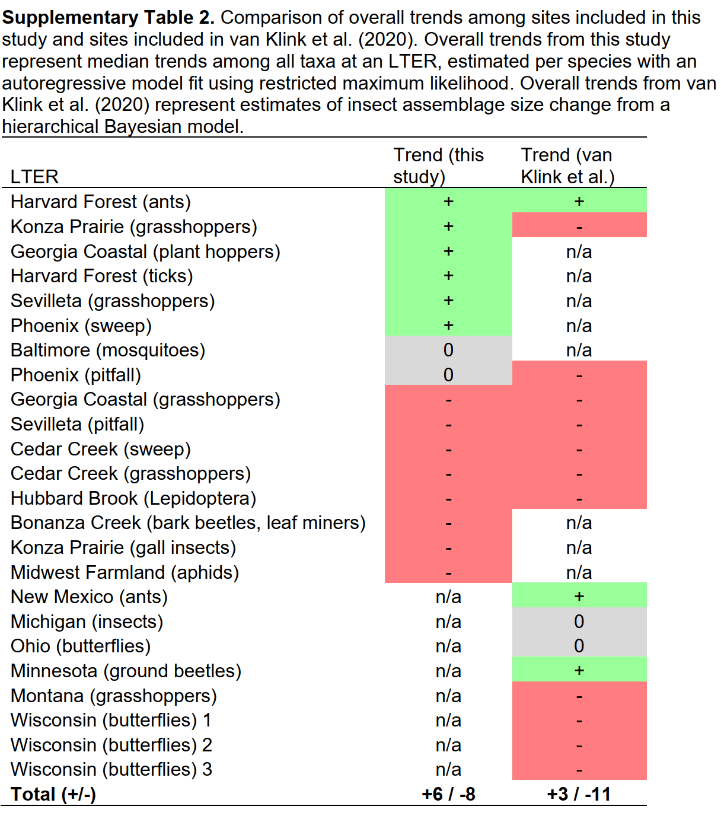

The Moran study, published in August 2020, examined four to 36 years of data on arthropods (insects and other invertebrates) collected from US Long-Term Ecological Research sites located in ecoregions throughout the country. The finding: “There is no evidence of precipitous and widespread insect abundance declines in North America akin to those reported from some sites in Europe.”

The data show that while some taxa declined, others increased, and the vast majority had stable numbers. The overall trend, they concluded, is “generally indistinguishable from zero.” Neither could the authors attribute population changes to any specific cause, including insecticides. The study compared the data on insect populations to “human footprint index data” which includes factors such as pesticides, light pollution, and urbanization.

Credit: Sharon Dowdy, University of Georgia

Credit: Sharon Dowdy, University of Georgia

In the press release announcing the study — “Insect Apocalypse May Not be Happening in the US” — University of Georgia postdoctoral researcher Matthew Crossley stated, “No matter what factor we looked at, nothing could explain the trends in a satisfactory way.”

With headlines relentlessly heralding impending doom for insects, it’s unsurprising the results left the authors “perplexed.” As Mann later wrote:

At first, we thought we were missing something. We tried comparing different taxonomic groups, such as beetles and butterflies, and different types of feeding, such as herbivores and carnivores. We tried comparing urban, agricultural and relatively undisturbed areas. We tried comparing different habitats and different periods of time.

But the answer remained the same: no change. We had to conclude that at the sites we examined, there were no signs of an insect apocalypse and, in reality, no broad declines at all.

The discrepancies between van Klink et al. and Moran et al. on North American trends can be attributed to a few variables, researchers say.

- Four of five sites included in Moran but not by van Klink showed increased abundances, counterbalancing decreases found at sites included in both studies

- van Klink’s method of measuring abundance gives inordinate weight to “a relatively small number of numerically dominant species”

- Coverage of the data is greatest only in the last few decades, a period where van Klink found a reduction of the trends seen in earlier decades

The robustness of the Moran study data suggests the insect population story is much more complicated — and less dire — than many headlines suggest. If a thorough examination of the data on one continent can lead to such a dramatically different and more hopeful conclusion, broad trends in the vast, highly diverse and relatively unstudied continents of Asia, Africa, Latin America and Australia cannot be characterized through extrapolation with any assurance.

Challenging Moran’s data

The Moran paper received some pushback from scientists who said that it suffered from inconsistent sampling methods and modeling errors (and in some cases, differences of opinion). The authors welcomed the dialogue and responded to the critiques this past April.

Ellen Welti pointed out Moran et al. had failed to correct for sampling issues. In response, the authors re-curated the metadata to maintain per-sample arthropod numbers and used several different approaches to repeat the analyses of abundance and biodiversity trends per site. He found that, while there was broad variation between taxa and sites, there wasn’t an overall pattern of increasing or decreasing populations.

Welti also accurately noted that there was a coding error in the original study that removed several time trends from one of the sites, and three of the datasets inappropriately included experimental plots. But even after correcting for the coding error and excluding the experimental plots, the overall results did not change.

Marion Desquilbet raised technical concerns over which data should have been included. They were relatively minor issues, and the Moran team responded. Reflecting an abundance of caution, they repeated his analysis, but the patterns remained the same.

Even after the re-evaluation, accounting for potential differences in sampling over time and excluding potentially problematic time series, the Moran study results remained largely unchallenged: there isn’t evidence of broad insect declines across North America. Based on the only extensive evidence available, insect populations on the whole and in the US (which Goulson and other crisis promoters have portrayed as the epicenter of the impending global ecological melt-down) are stable.

Cycle of bias?

The overall paucity of data provides an opening for alarmists to speculate, and Goulson and others have taken advantage of that. But why is the data so fragmentary? Moran and co-authors attributed the lack of corroborating studies supporting the consensus view that insect populations are mostly stable to what he calls “publication bias … more dramatic results are more publishable. Reviewers and journals are more likely to be interested in species that are disappearing than in species that show no change over time,” he wrote in the Washington Post.

It’s a reinforcing feedback loop, with journalists playing a key role in this disinformation cycle. Scientific publications are more likely to publish reports of declining species. Then, when researchers search for data, “declines are what they find. ”The media often seizes on incomplete or even biased conclusions to build a compelling narrative — an insect apocalypse or insectageddon or zombie-like resurrections of debunked reports of birdpocalypses and beepocalypses.

The result is that enormously complex issues often are portrayed in cartoon terms. Conventional farmers are invariably cast as the “black hats” who dare to use advanced tools of biotechnology and targeted synthetic chemicals; they are harshly contrasted with crusading ‘white hat’ scientists and advocacy journalists cast as partners with the Earth and Nature. Independent scientists are increasingly frustrated. As professors Sanders, James and O’Hanlon have written, there are consequences to simplistic frames:

We disagree with the catastrophic decline narrative, not the concept of population declines or that individual studies have shown declines in some places. Declines are probably happening elsewhere too, but we have no data to prove it. Yet other insects are not declining, and some are increasing in population size or range distribution. New species are being named every year, most of which we still know nothing about.

Presenting the global decline narrative as consensus or fact is simply misrepresentation of science. By continuing to promote the narrative, we may suffer from confirmation bias, potentially encouraging scientists to look for evidence of declines in their data where they may be none.

It is perhaps too much to hope that journalists would have learned their lesson after chasing so many ‘verge of extinction’ tales over the past 15 years that proved false. That’s why more independent studies like Moran et al. are needed to break the cycle of bias.

And maybe a little restraint from pack journalists. Keep that in mind over the next few months when Goulson launches his ‘insect Armageddon’ documentary and book tour media blitz.

“Let’s move on from the decline narrative,” Manu Sanders and her colleagues plead. “We need less hype and more evidence-based action on the priorities we can address right now.”

Jon Entine is the founder and executive director of the Genetic Literacy Project, author of 7 books and winner of 19 major journalism awards, including two Emmys. Twitter: @JonEntine