How do crickets, grasshoppers and their relatives make noise?

Katydids are a group of insects that are part of the Orthoptera, which includes all crickets, grasshoppers, and grasshoppers. These animals create songs through stridulation, rubbing body parts such as wings and legs together to produce sounds.

Generally, males use these sounds to attract females during the summer breeding season, although females of some species will stridulate under certain circumstances.

The last time the sound of P. obscura was positively identified in the wild was over a century ago. The only known specimen of the insect was presented to the museum by British Army officer Sir John Bennet Hearsay, and the species was later scientifically described by Francis Walker in 1869.

Despite repeated attempts, the species was never seen again. This is partly due to its labeling, as the specimen was said to be from ‘Hindustan’, which the researchers believe is generally synonymous with the area of India under British rule.

That was until 2005 when two female insects that looked similar to the male P. obscura were collected from Tibet. Due to the sex differences between specimens, it cannot be determined with certainty whether these insects are part of the same species or a closely related species.

If found living together, it could help confirm the identity of the Tibetan Katydids.

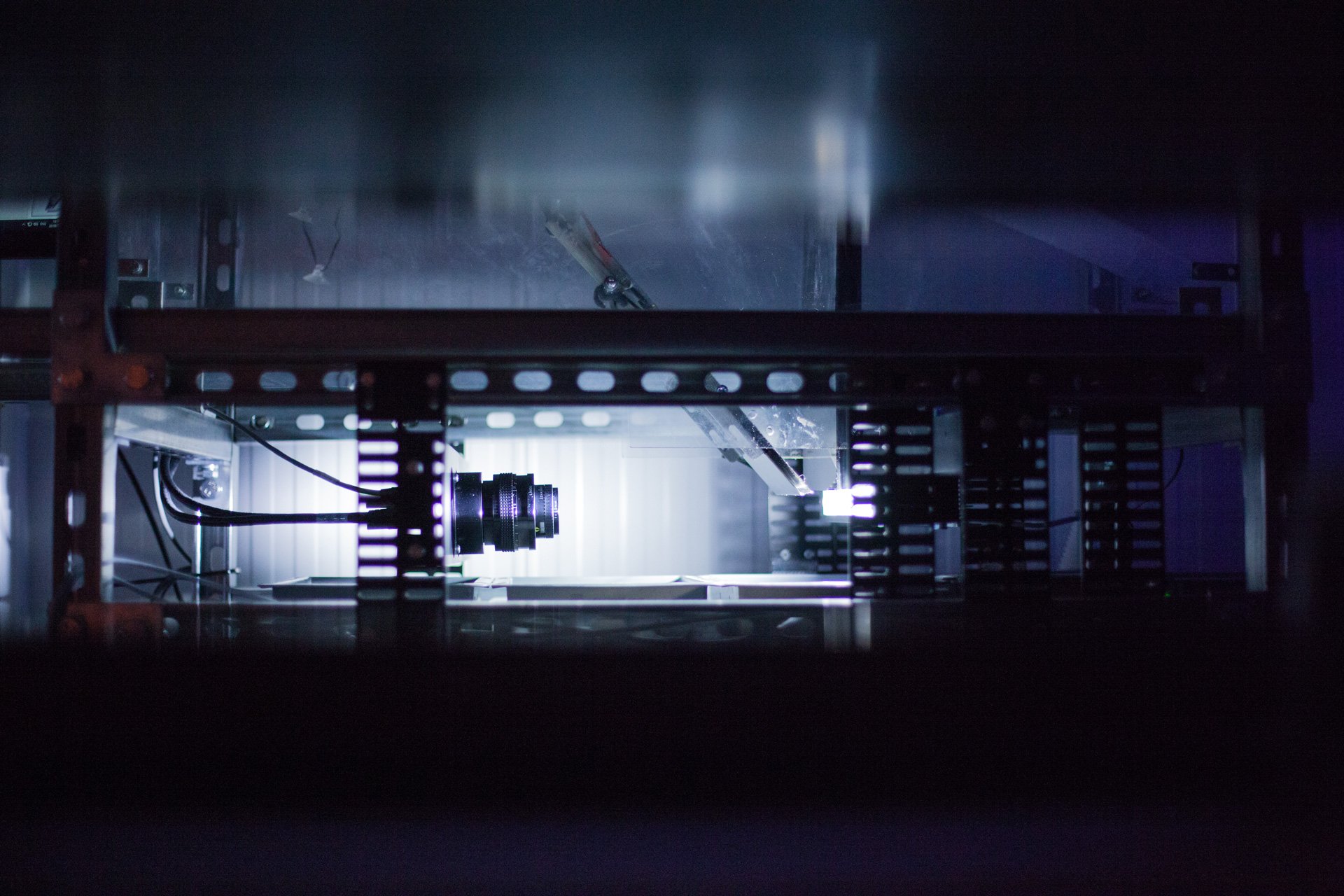

To find out more about where the species might still live, the researchers created 3D images of each wing and determined their resonant frequency. With this information, the team was then able to reconstruct what the insect’s song might have sounded like.

“Insect sounds can be linked to its evolutionary history,” says Ed. “They can study why species have specific song frequencies to avoid overlap and how song structure reflects their environment and evolution.”

In the case of P. obscura, its low-pitched song can be explained by its environment. Bats tend to avoid cold areas through migration and hibernation, which would allow the katydid to fly freely without the risk of being eaten.

The cold climates of northern India and Tibet could therefore be suitable locations for this insect, which could potentially help scientists rediscover the species.