SINGAPORE – The abundance in the depths of the ocean often distracts attention from what is on its surface.

But an enigmatic insect that lives on the ocean’s skin has helped an international team of scientists uncover the layers of how environmental changes can affect wildlife.

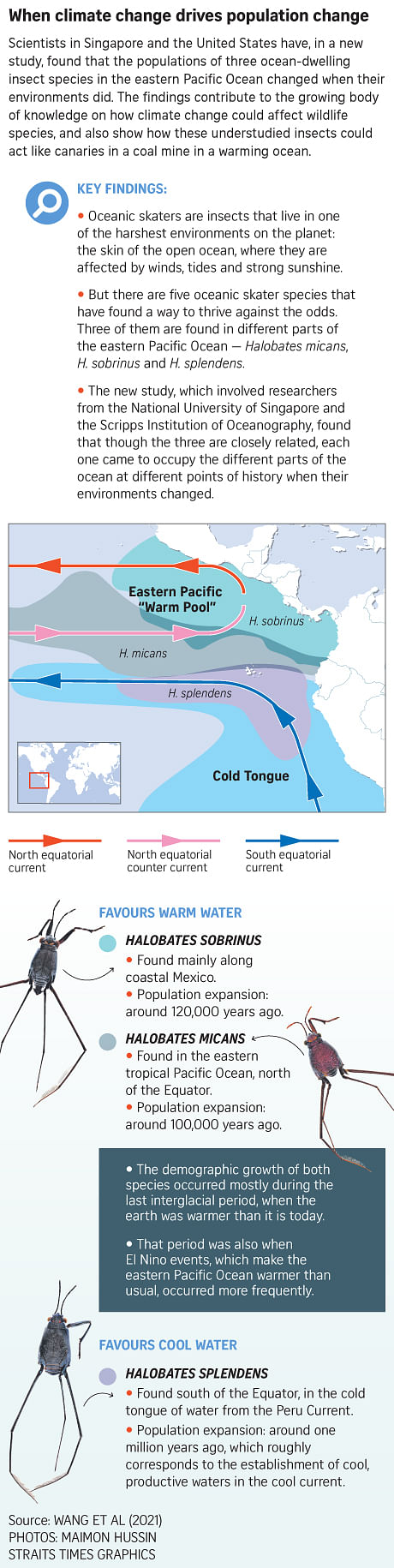

A new study found that the population growth of three oceanic ice skating species in the eastern Pacific coincided with changes in the local climate.

The research paper from researchers at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego was published today (September 6) in the journal Marine Biology.

Their results show that oceanic skaters can function as canaries in the coal mine in a warming ocean, using population trends as indicators of how open oceans – a habitat difficult to monitor due to their inaccessibility and difficult to monitor due to their inaccessibility – are changing.

The study could also help scientists better understand how climate change can affect insects and marine organisms.

NIS marine biologist Huang Danwei, one of the study’s authors, said, “Insects could include parasitic and even disease-transmitting insects so we could understand whether their populations would significantly overlap with human-dominated areas to pose a problem to our health will .”

Oceanic skaters are not easy insects to study.

Their fondness for the open ocean means specimens can only be obtained through expensive oceanic expeditions, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars a day.

In 2006, Dr. Lanna Cheng, Seafarer Scientist at Scripps Oceanography, said her contacts at the United States’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration were planning an ocean expedition to monitor the activities of seabirds, whales and dolphins in the eastern Pacific, from California to South America.

“One of the senior scientists on board was interested in flying fish. So I said if you collect flying fish and illuminate the surface of the water, you must be able to attract my insects too,” said Dr. Cheng. who has studied these creatures for over five decades.

“And he said, ‘Oh yeah, sure, no problem’.”

This expedition produced nearly 400 specimens of oceanic skaters of three types.

Dr. Cheng, who did her bachelor’s degree at the NUS, maintained close contacts with scientists from her alma mater.

In 2017 she sent the skater samples to a laboratory in NUS, where Dr. Wendy Wang worked.

Graduate student Marc Chang (left) and Assistant Professor Huang Danwei hold samples from oceanic skaters at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. ST PHOTO: TIMOTHY DAVID

At that time, Dr. Wang was on a project to find out if species could only be differentiated by a fragment of their genome – much like barcodes can indicate the type of product being sold.

Dr. Wang found the barcode worked, but also found that there were population-wide differences in the barcodes of the three different types. These genetic variations between species illustrate different histories of population growth and development in ancient times.

Dr. Cheng then drew in Professor Richard Norris – her paleoceanographic colleague at Scripps Oceanography – and other NUS genome experts, including Dr. Huang and his PhD student Marc Chang.

By comparing the genetic data with the fossil record, the researchers found that the oldest of the three species, Halobates splendens, experienced a population expansion nearly a million years ago.

This species is found today in the Peruvian Current – the rich, productive waters that arise off the coast of South America. Climatological data showed that this physical feature of cold surface water originated a million years ago.

The two younger species, Halobates micans and Halobates sobrinus, which are found today in the warm, relatively unproductive waters off Central America, increased 100,000 to 120,000 years ago.

A scientist holds up a sample of Halobates splendens found off Peru. ST PHOTO: TIMOTHY DAVID

The populations of both species grew when El Nino climatic events caused warm seawater to pour into the eastern Pacific.

El Nino events were particularly strong in this region about 100,000 years ago, which coincides with the time when these species developed their modern genetic patterns and population sizes.

Prof. Norris said, “Genetics shows that the three species we studied each had periods of population growth that correlate incredibly well with geological evidence of the formation of the current systems in which they live.”

The researchers now plan to take a closer look at the genetic makeup of oceanic skaters, who are resilient creatures exposed to intense sunshine and gusty winds.

“The ability of their body covering or cuticles to protect their internal organs from heat and UV damage and to survive violent storms and in this unique habitat where no other insect could find food demonstrates their unique ecological role in the ocean” said Dr Wang.

“These properties make them fascinating subjects for materials science and extreme biological adaptations.”