Rodents like house mice (Mus musculus) are not only pests in the home, they can also seriously damage native ecosystems.

Lord Howe Island, for example, hosted up to 150,000 introduced rats and 210,000 introduced mice, which devastated the island’s native wildlife before intense eradication efforts were made. It was declared successful earlier this year, although surveillance for survivors continues.

Read more: Invasive predators are eating the world’s animals to extinction – and the worst is near home

However, new research suggests that the success of pest eradication may depend on the personality of individual animals within a species.

More courageous, active, aggressive, or social people are more likely to interact with bait, traps, or new objects and foods. This allows them to be removed quickly.

On the other hand, it may take longer to catch shy or less active individuals.

Why is that so important? Good to start with, animals that actively avoid extinction will reproduce and repopulate.

If the personality traits of these survivors are reflected in all or even most of the offspring, we could face a pest population that is incredibly difficult to remove. This is what our new research wanted to find out.

Islands like Lord Howe Island off NSW are sanctuaries for a range of wildlife not found anywhere else in the world.

Shutterstock

When the repayment efforts fail

Australia is home to more than 8,300 islands that provide refuge to unique species not found anywhere else in the world, including species that are now extinct on the mainland.

Introduced mammalian pests, particularly rodents, pose a tremendous threat to island species, which often evolve without predators. They don’t recognize these introduced mammals as a threat, which makes them easy targets.

For example, a 2010 study observed house mice literally eating live albatross chicks on Marion Island, near Antarctica. Neither the chicks nor the parents showed any defensive or flight behavior.

Read more: Wild animals run amok on the Australian islands – Here’s how you can stop them

Eradicating introduced pest species is the ultimate solution if we are to protect native island ecosystems.

However, eradication efforts are only effective when every animal in a population is eliminated. While most failed efforts are unlikely to go unreported, an average of 11% of rodent eradication attempts fail. In house mice in particular, failure rates can be up to 75%.

Nesting albatross on Marion Island where chicks have been found to be eaten by introduced house mice.

Shutterstock

When efforts fail, pest populations recover quickly. A 2016 study found that around 50 rats survived an attempt at extermination by avoiding bait on Henderson Island in the South Pacific. Within just two years, the population had exploded into around 75,000 animals.

Develop personality traits

So if animal behavior affects whether a person steps into a trap or takes a bait, how much of the parent’s personality is reflected in the offspring?

If you’ve thought about the similarity between parents and children – both in humans and in our animal companions – then you know that some offspring behave just like their parents, while others are very different.

Personality traits arise through a combination of experience, learning from parents, and genetic inheritance.

Humans have selectively bred pets, including dogs, cattle, and horses, for preferred personality traits such as docility.

Read More

Studies in laboratory animals, including mice and chicks, have shown that selection of preferred traits in parents can result in high levels of these traits in the offspring within a single generation.

However, can this immediate generation response occur in wild populations?

What our study did

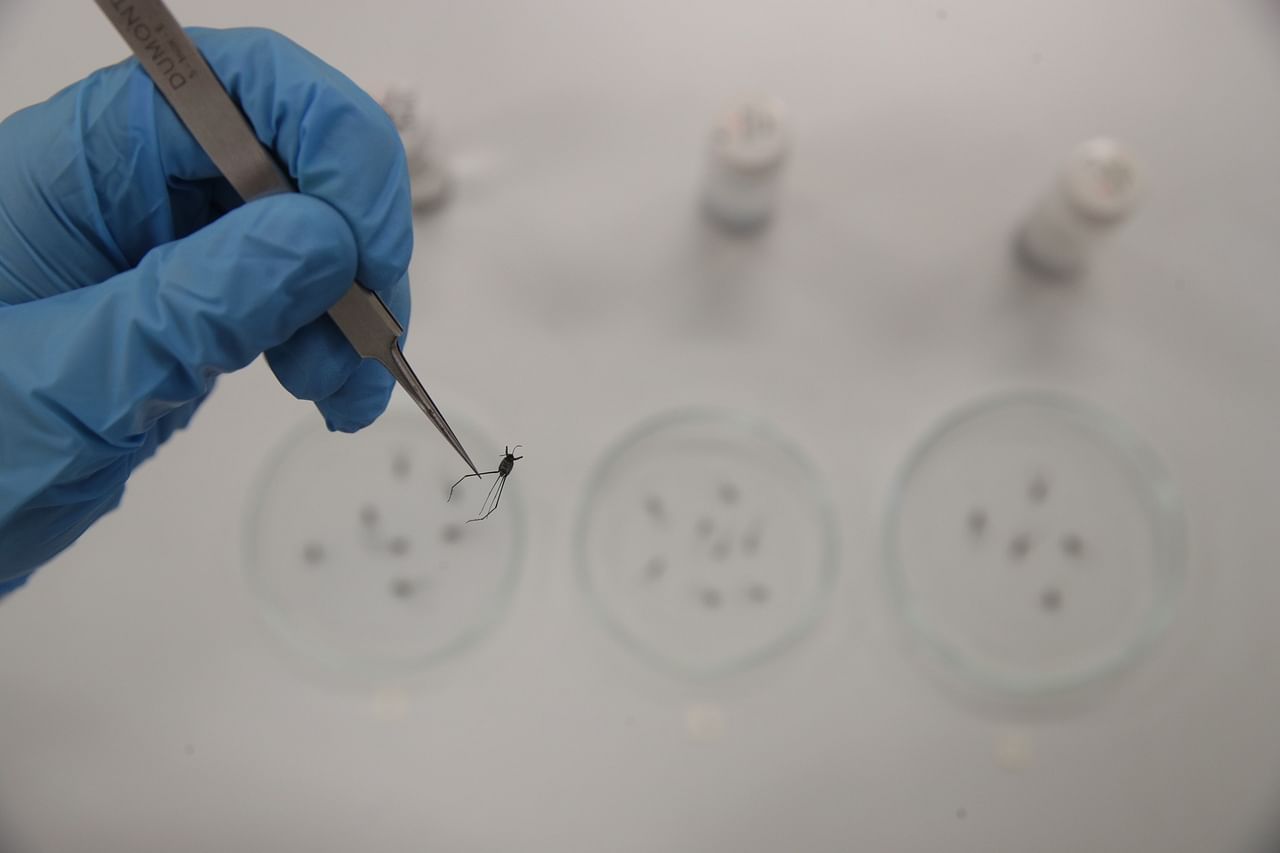

To untangle this web, we used house mice as a model species and mimicked a failed eradication in which remaining mice (the potential survivors) were selected based on biased personality traits.

A mouse in our study is trapped in a trap.

Kyla Johstone, Author provided

After catching wild house mice, we tested personality traits by filming their behavior in a modified outdoor arena. Mice that frequently moved between compartments and into light compartments (which is a risky scenario for a small nocturnal rodent) were viewed as “highly active-bold” individuals.

Based on their behavior, we then grouped individual mice into populations: individuals with high active bold, individuals with low active bold (shy individuals), and intermediate individuals.

Read More: How To Know If We Are Winning The War On Australia’s Fire Ant Invasion And What To Do If We Are Not

To closely mimic the wild conditions, we released the populations in large outdoor yards and let the mice breed for a generation. After reclaiming every single mouse from the farms, we tested the offspring for the same personality traits.

The good news

Interestingly, although the parent populations had severe personality biases, there was a wide range of personality among the offspring of each population. In other words, brave mice did not necessarily produce brave offspring, nor did shy mice, shy offspring.

A juvenile mouse from our study. Mice born to shy parents did not necessarily have shy personalities.

Kyla Johnstone, Author provided

That was comforting news. However, demonstrating that house mice do not have generational bias does not mean that they cannot be found elsewhere or in other species. Our study is an important step in examining this concept in other invasive species and across generations.

At least for the extermination of house mice, our results suggest that even if all surviving individuals had a similar personality, a broad spectrum of personality should emerge from the next generation.

This suggests that we are unlikely to face a population that cannot be removed and that we can focus on improving success rates for these difficult-to-remove individuals and species.

Read more: “Compassionate Protection”: Just because we love invasive animals doesn’t mean we should protect them